To Read or Not to Read

What I want to examine is the why and how of learning the skill of reading, and some suggestions about what you, the reader, might consider to help put us back on track toward a healthier, happier, and better informed adult cohort that we're now guiding in their formative years.

American Education at a Crossroads

There seem to be two driving forces jostling each other for attention in American education:

- Cultural Concerns—specifically topics related to Woke or DEI

- Fundamentals—the Trivium and Quadrivium that broadly concern language and words and number and quantity

Indeed, Rahm Emanuel, is lately making noises similar to a Presidential Candidate testing the waters. For example:

'I don't want to hear another word about the bathroom. You better start focusing on the classroom,' Rahm Emanuel told Bill Maher on Friday[1]

Specifically focusing on Chicago, Emanuel also has said:

“We have the worst reading scores for eighth graders in 30 years, and nobody – not a governor, not a mayor, not a president, not a secretary of education is talking about it. We’re all wrapped up.[2]

This criticism isn’t just about politics—it points to a deeper struggle over what education is for, and whether we’ve lost sight of its foundation.

In Simpler Terms

Over time, fundamental skills that build character and permit a meaningful, productive and fulfilling adulthood, have been neglected in favor of trendy theories and outright untruths by a small but vocal group of activists. Space and time constraints preclude discussing all facets of this serious decline in educational and cultural focus. This essay instdead concentrates on a single aspect of the overall fabric of declining standard.

Reading is but a single part of the entire puzzle. What I want to examine is the why and how of learning the skill of reading, and some suggestions about what you, the reader, might consider to help put us back on track toward a healthier, happier, and better informed adult cohort that we're now guiding in their formative years.

Questions Worth Answering

I was prompted to write this post by two articles that appeared this morning in The Free Press, a daily publication that sends me a morning newsletter daily. For my money, it's one of the best on-line publications out there for a variety of reasons, but that discussion is for another time.

These articles sparked more than casual interest for me—they raised fundamental questions about why we read at all, and how we teach it.

Why Read At All?

Writing in What Happens If No One Reads, Author Spencer Klavan recounts some interesting observations regarding earlier technology "revolutions," such as this:

The strange thing is that, once upon a time, professors worried that reading would dull the mind, in the same way we now worry that screens will. In the fourth century BCE—shortly after it became trendy for the chic philosophers of Athens to sell and distribute written copies of their lectures to the elite young strivers of their day—Plato wrote a dialogue, Phaedrus, in which Socrates grouses that gadgets like papyrus are making students lazy. He talks about written texts as if they were a kind of external hard drive for the mind, retaining information so that you don’t have to.[1]

Klavan then goes on to observe the irony in Plato's own complaint, having been made in writing! This ancient anxiety feels familiar today, as many now warn that AI will weaken thought just as papyrus was once accused of weakening memory.

Klavan's argument in favor of actually reading a text rather than depending on AI to generate a summary, or even for using CliffsNotes or other synopses, hinges on deeply human capacities for empathy and emotional impact. AI cannot summarize a passage that brings great joy or sorrow to the reader who actually reads the passage, in context, and for whom the text has unexpectedly profound meaning.

This is where the case for reading becomes persuasive—not just as a skill, but as a deeply human practice that shapes how we feel, not just what we know.

But I can no more summarize the article than can AI; you must read it for yourself—to understand it, absorb its meaning, and experience the right-brain impact good prose is able to engender.[1:1]

How to Teach Reading

In this article, I Taught My 3-Year-Old to Read ‘The Hobbit.’ Plus. . ., largely focused on parenting, author Erik Hoel tells of the historical significance and success of tutoring as the most effective way to educate children. As with the Klavan article above, he references antiquity by noting that one of the greatest statesmen of all time was the philosopher-king Marcus Aurelius:

Never was a boy so persistently educated. . . . Marcus liked games and sports, even bird snaring and hunting, and some efforts were made to train his body as well as his mind and character. . . . Four grammarians, four rhetors, one jurist, and eight philosophers divided his soul among them.[2]

Hoel goes on to list numerous other great thinkers and intellectuals that punctuate the historical record, at the same time noting:

As the name suggests, aristocratic tutoring was something reserved mostly for aristocrats, which means—no way around it—it was deeply inequitable.

Hoel then describes the approach he used with his own son to teach him to read The Hobbit at the age of three. The irony here is that this was not a deeply inequitable approach.

These examples remind us that while history is full of privilege, the principle behind tutoring—close, personal guidance—is accessible in smaller ways today.

I found myself thinking that one-on-one tutoring was not necessarily confined to reading. A little reflection on some of the great musical, artistic, mathematical and scientific talents that have benefited mankind over the centuries will probably suggest more examples where similar approaches have resulted in stellar results. Mozart, whose musical talents were cultivated by his father is one. The Jussen Brothers, dual pianist brothers both of whose parents are successful musicians are another. In a field like IT, that I follow closely, one of the best bloggers and teachers I have encountered is Milan Milanović (no relation) whose father also had a long career in IT.

The article wraps things up by asking:

Can the individualized tutoring that was so effective for us ever scale?

That’s the challenge—how do we bring the benefits of one-on-one attention into a mass education system that often feels impersonal and overwhelmed?

The somewhat oblique answer is:

People, including myself, are beginning to realize that the real reason to deploy the best and most effective methods of education is to chip away at the totalizing time suck our inefficient school system has become.

https://www.thefp.com/p/what-happens-if-no-one-reads-culture-education ↩︎ ↩︎

Durant, Will; The Story of Civilization: Vol III, Caesar and Christ, in https://www.thefp.com/p/i-taught-my-three-year-old-to-read-tutoring-education-culture ↩︎

What's to Be Done?

Hoel's recurring comments about inequity reflect a focus on parents' ability to pay in cash for quality tutoring services. While it is true that this can be a barrier, it's not the only path toward improving our children's reading skills or education in general. Here are a few suggestions.

At this point, reflection needs to turn practical. What can each of us do—parents, elders, citizens—to build stronger readers?

As a Parent

- Spend Quality Time teaching your kids to read. For starters, take a look at How to teach your two-year-old to read

- Read aloud early and often. Children absorb the rhythms of language long before they can read themselves.

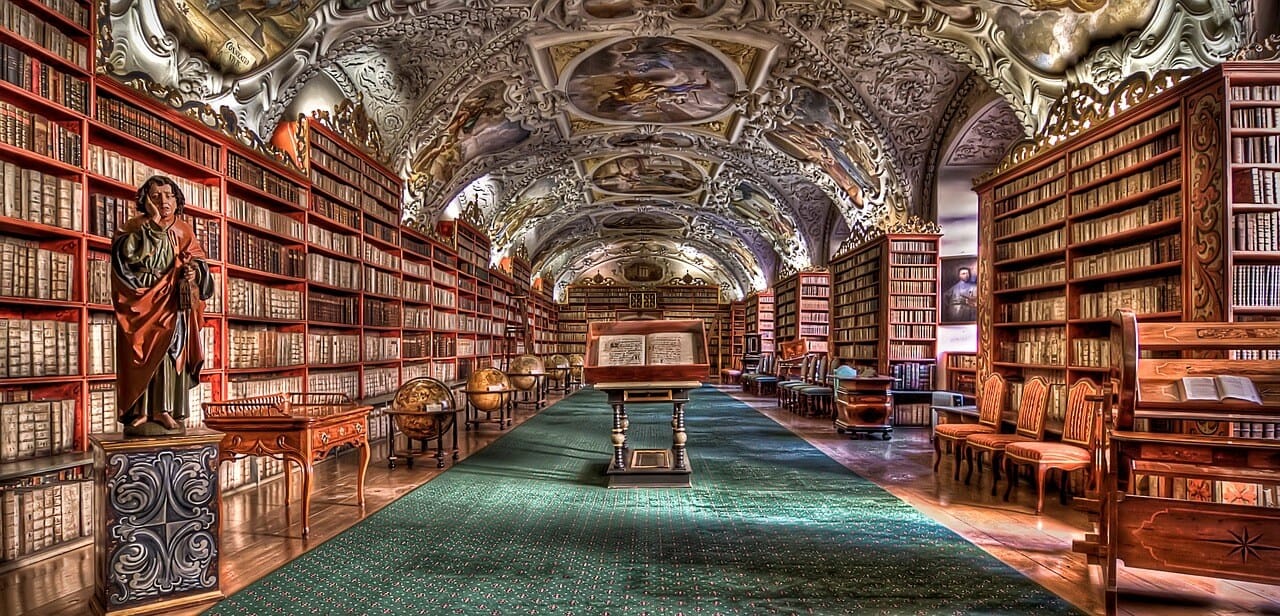

- Make books visible. Keep them within reach in the home, in classrooms, and in community spaces.

- Model the habit. Children imitate what they see. Let them catch you reading.

- Tell stories. Oral storytelling builds vocabulary and imagination.

- Support teachers and libraries. Even small gestures of encouragement or donations of books can have lasting effects.

As An Elder

If you're at the end of your working years, or nearly so, you will shortly become retired or semi-retired. This might be a great opportunity to find a new career and add meaning and legacy to your golden years.

- Local Schools often need tutors and mentors.

- Your Own Children's Children — give your grandchildren the gift of attention through reading.

- Internet Tutoring — one-on-one tutoring is now possible across the world.

As A Citizen

The responsibilities of citizenship never cease.

- Participate in parent-teacher groups.

- Vote with education in mind.

- Civic Groups like Freemasons or Rotarians often support education.

- Church Groups can also play a role.

Conclusion

We live in an age of rapidly changing technological advancement; this has resulted in a reordering of priorities and a shift in focus toward ever increasing dependence on technology as a solution to all of mankind's pain-points and ills. This is a dangerous and hubristic posture to assume, especially given the relative youth of our technologies and their application to the quality of life.

The Free Press pieces reminded me that the real debates about our future are not only about budgets or technologies. They are about whether we will pass along the most basic skill that makes every other kind of learning possible: reading. Two thousand years ago, skeptics warned that papyrus would weaken memory. Today, some warn that AI will weaken thought. Neither outcome is inevitable. What matters is the foundation we lay for our children.

By staying connected to the foundational principles of language and words, we can provide for peaceful and effective implementation of these new wonders of our modern civilization while maintaining contact with the very basis of human existence that has sustained us for millennia.

Reading is one of the fundamental and perhaps most important skills needed to navigate today's sometimes chaotic and rapidly shifting currents. It is, also, one of the most satisfying things a person can employ for edification, self-improvement, or just plain entertainment.

If we place books in young hands, if we read aloud and tell stories, if we let children see that words matter, then literacy will remain the bedrock of our culture no matter what new tools emerge. This is not glamorous work, but it is the most important kind of work—the quiet, steady work of building readers. The future will be shaped by those who can read with depth, think with clarity, and imagine with courage. That is the gift we owe the next generation.

Give your kids, or anybody's kids, the gift of reading.