Dear Brian,

What follows was prompted by an email from one of my oldest and most treasured friends, Brian—a musician, composer and lyricist.

Foreword

What follows was prompted by an email from one of my oldest and most treasured friends, Brian—a musician, composer and lyricist. Brian wrote:

More and more, I wish I had continued my classical music studies. You are quite knowledgeable in that field--What books/recordings can you recommend to someone who is not a beginner but needs to brush up?

What follows is my reply to that query.

You asked me for book recommendations as a means of brushing up on classical music. We share interesting interests in music, as well as some diverging ones. For you it seems to be jazz, pop and Broadway, with some experimental lately showing up in your emails to me. For me, it's more classical, Broadway, C&W with some classic jazz to add a little pizzazz. That plus you're an experienced composer and lyricist while I abandoned professional aspirations long ago. So together, we cover a broad range of potential topics and experience.

Nobody ever asked me about my musical path before, so I had to think about it a bit. Here's what I can recall.

As a general comment, let me say that whatever I have learned over a lifetime about music in particular, has been largely serendipetous and opportunistic. A little here, a little there, over many years of encounter. I didn't plan to spend as much time as I did involved in musical activity; it just happend to me.

Childhood Wanderings

I started by taking accordion lessons some time before high school. I still remember the Mayfair School of Music in that pie-shaped building at the corner of Lawrence and Elston in Chicago. I was terrible at accordion, but I did learn about the diatonic scale, and how to read notes and match the notes to the piano keyboard on the instrument.

High School Wanderings

High school saw me enter the band, under a conductor and teacher named Clayborn Harvey. At the same time, I started taking clarinet lessons with a teacher named Dave Snapp who taught me clarinet and later saxophone. Snapp was an ex US Navy musician with a broad background and played jazz clarinet, sax and flute along with being able to teach Kröpsch Etudes and Mozart Concerti.

Snapp introduced me to the etudes of Fritz Kröpsch—hundreds of them, it seemed—all engineered to frustrate your fingers and sharpen your technique. They were merciless but unforgettable. It was a productive four years.

In high school I also started playing with what was then a pretty rudimentary symphony orchestra of students. Orchestra rehearsals were really string rehearsals, but for concerts they drafted winds and percussion from the band department so I got to play both orchestral and band pieces during high school. Likewise, the chorus teacher was ambitious enough to mount operettas and other choral works that required an orchestra (Seven Last Words of Christ, The Messiah, Pirates of Penzance, etc.) So that added to my breadth of experience.

There was a jazz ensemble, but I never got to play with it, especially since my sax skills were far behind my clarinet skills and stock parts for big jazz bands were typically 5-part sax, trumpet, trombone, keys, percussion. The saxes doubled clarinet and flute, but primarily what they needed was a good jazz saxophonist, which I was not.

Northbrook Band

Some time during that period I joined what was then the Northbrook American Legion Band. The conductor was John Paynter, of Northwestern University fame. I don't know how I heard about it or why I bothered to pursue it, but I'm glad I did. Paynter was an incredible experience for the years I played under him.

Over the years, as Paynter developed the idea of a community band that performed at a very high level of musicianship, it evolved into the the North Shore Concert band of today, under the direction of Northwestern Professor of Conducting Emeritus, Mallory Thomas.

This present reflection reminded me of Alan Andreasen, a kind trombonist I knew in high school who also marched with the Northbrook band. After graduation, he moved to San Francisco, found love, and lived openly in a way that many of us couldn’t imagine back then. He died young, but I remember him with warmth and gratitude. Music gave us a shared language before we had the words.

Northwestern University

Then, on to Northwestern to major in music. This is where I really failed, although I did make it through one quarter of being a music school student. I played in the marching band, affectionately called NUMB (Northwestern University Marching Band) in the days when it was all male and the motto was "P&G", which stood for "Piss and Guts" or "Paynter and God (in that order)" depending on who you wanted to shock. I'm now obviously considered a NUMBALUM.

Paynter's goodbye to me was that he thought I'd make a fine music educator, confirming my decision to move on to other paths.

Biggest takeaway from Northwestern was the opportunity to play contrabass clarinet with the Symphonic Wind Ensemble when it played the Hindemith Symphony for Band in Bb. Paynter was a composition major as an undergraduate, and had an intimate knowledge of all levels of composition and the uncanny ability to explain it during rehearsals. The Hindemith Symphony is a pinnacle of counterpoint, with a finale of a double fugue with a third added theme. Once you understand what Hindemith was doing, and played it with that in mind, it became one of the most exciting things I have ever experienced in the Symphonic Band repertoire. Paynter's detailed explanation of what Hindemith was doing and how he wanted it played was a revelation.

A close second was the Berlioz Requiem mounted by the NU Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. It rivaled anything that the BBC has presented of this piece at the annual Proms at Royal Albert Hall. Gigantic in scope and filled with the sadness, tranquility and terror common for the Roman Mass for the Dead set to music in the 19th Century. My part? Two notes, in the entire piece, played on the largest tam-tam I have ever seen. It happens in the Tuba Mirum, as you might expect, with an enormous brass fanfare from brass ensembles in the four corners of the auditorium, that rises to an incredible V-I resolution with that gong leading the orchestra and chorus of several hundred into Tuba, tuba mirum, spargens sonum... Per sepulcra regionum. It gives me goose bumps to this day.

Wabash College

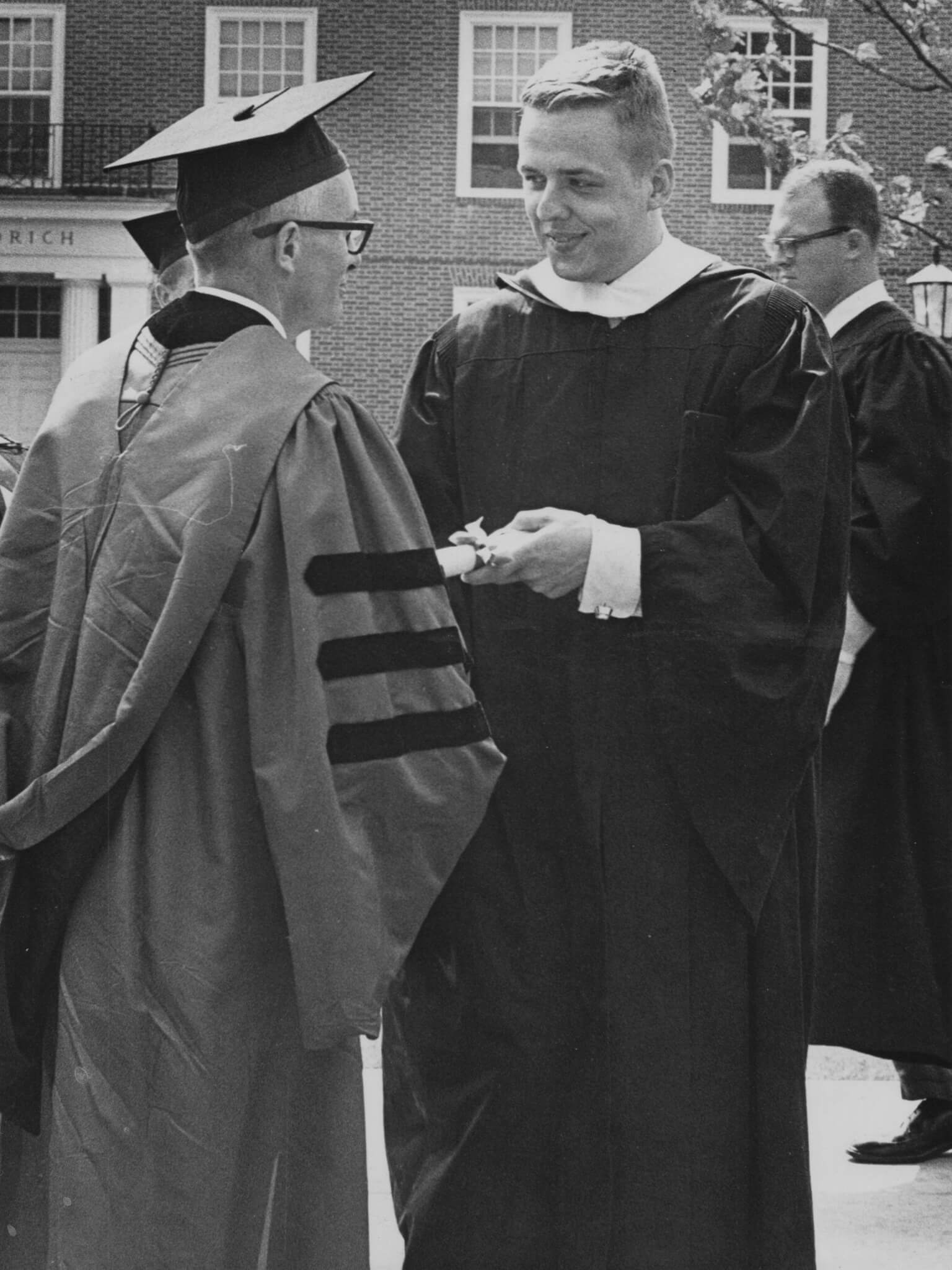

I received my undergraduate degree from Warren "Butch" Shearer, acting President, in 1966. Pep band was a popular music activity for some of us.

I eventually landed at Wabash College, where music was hardly anybody's interest. However, I did play in the Pep Band for athletic events; we were a rag-tag group of wannabe's but spirited, and we could play the fight song from memory, and that's all that mattered. Old Wabash is probably the world's longest fight song, and I can sing it all from memory—a requirement of all new students who expect to be socially acceptable.

As far as Wabash goes, music took a second seat to theater, although I did play a baritone saxophone in a production of Meredith Wilson's Music Man that was reasonably successful, but certainly not up to NU standards for musical, theatrical or dance quality.

I became a stage manager. At Wabash one of the problems facing a stage manager back then was getting actors to come to rehearsal on time; some of them would crawl into their bunks in fraternity dormitories and just forget to get up. I quickly learned who the slackers were, and learned which bunks they slept in. (Some guys even seemed to rotate bunks, so if somebody was napping in yours, they just took somebody else's.) Once I got all the actors to rehearsal I was able to settle in and behave like a real stage manager, and it exposed me to the creative process of theater, and Charlie Scott, the Theater Director, was instrumental in grounding me in an appreciation of theater.

Railroads

Strangely, my summer jobs while at Wabash were always working as a brakeman for a railroad, first the C&NW and for the final four summers, The Milwaukee Road. I loved it. I still love railroads. But there was no time for music, theater or any art form to speak of during those summers.

The five years I spent on high-iron left an indelible mark on me; to this day I admire working men and what they contribute to our way of life. It taught me physical endurance and probably most significantly, what we know as situational awareness—the ability to focus on a task but remain alert for situations that might affect your or other's safety.

Chicago Wanderings

I eventually left the railroad, one of the truly great mistakes of my young and naive self, and went to work in various IT jobs.

Then, one day I was walking down Michigan Avenue on Chicago's lake front and passed Orchestra Hall, where a poster proclaimed that evening's concert would be Ottorino Respighi's Pines of Rome. On impulse, I walked in and snagged a front row first balcony ticket for hardly anything. It's hard to describe how that performance impacted me. The CSO is definitely at the top of the world's stack of virtuosic ensembles and Pines is one of the best examples of evocative tone poems ever conceived.

I saw the Roman Legions, advancing through the morning mists, silver eagles held aloft as they approached Rome along the Appian Way. I felt the earth tremble at their glorious entrance, and witnessed in my own mind, the power and glory of that long gone civilization. The last movement also begins with what is arguably the best-known English Horn solo in the repertoire. That final movement, The Pines of the Appian Way, has stayed with me ever since.

Since that performance of the CSO I have been an avid follower of Chicago arts and culture, especially musical performances and theater. I have served on the boards of two symphony orchestras and two theater companies over the years. I still attend performances as much as I can squeeze into my schedule.

Opera and Ballet have been late additions to my arts interests, making the complete triumvirate of the three great Chicago Performing Arts Gorillas complete: The Chicago Symphony Orchestra, The Lyric Opera of Chicago, The Joffrey Ballet of Chicago. To be certain, I shouldn't ignore great theater companies like Steppenwolf or Goodman, and even the downtown houses that feature Broadway road productions are deserving of mention. But somehow my inclination has always been either one of the Gorillas, or Chicago Store Front theater. I can't explain it, but perhaps the generally intimate experience of Chicago Store Front is somehow reminiscent of my undergraduate days, making attendance both a matter of artistic choice and nostalgia.

I worked in IT consulting for a time. I also tried operating a wholesale greenhouse in exurban Chicago, but was unable to make it financially viable. I became a gay activist, not in the modern militant sense, but more involved with community service and constructive persuasion.

But I didn't give up on music and the arts.

Honing the Razor

A few of the Grant Park Music Festival co-workers.

At one point I seriously considered returning to music as a career, except on the production end of things. I got a summer job as an Intern with the Grant Park Music Festival in Chicago's Millennium Park. It was a rather broadening experience. I was customer service by day, on the phone constantly with requests for information or service, and crowd control for performances, managing the main gate to the seating bowl, handing out will-call tickets, and generally trying to make sure VIPs were accommodated with requisite respect and courtesy. It was illuminating to handle that much responsibility at the Jay Pritzker Pavilion and have members of the Pritzker family come to my table to claim their tickets.

But other than the relentless flow of anxious patrons and occasional complaints, what a glorious summer of music it was. I met many other devotes of classical music who worked as ushers, or behind the scenes managers for orchestra and chorus musicians. I got to watch experienced conductors and music directors work and hone the performance. And I got to mingle with the musicians themselves, who are pretty much like normal human beings, except for their extreme focus on musical skills and perfections. They enjoy Chinese food or Poor Boys just like the rest of us.

Some performances are standouts. Of course, a season finale of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony is always a crowd-pleaser; standing-room only! Difficult crowd control, but once they settle in to this pinnacle of Western canon, they settle into rapt attention—a trance only broken by the final chord. The outdoor setting of the Jay Pritzker Pavilion only enhances the entire experience.

Carl Orf's Carmina Burana is another example of a thrilling and even foot-stomping season finale. The chorus is fully professional, under the direction of Christopher Bell. Performances of the Grant Park Chorus were among the high points of my experience at Grant Park.

The repertoire of that Festival organization expanded my appreciation of music significantly, extending as it does into some of the less formal or academic realms of music. A night of Broadway, or Independence Day, or popular music is a part of the regular schedule. All of it is masterfully performed by some of the best musical talent in America.

Face to Face With Opera

The Lyric does a little drag from time to time. The guy and his girlfriend are just opera lovers I saw in the lobby and the dress code? Well, it is opera, after all!

During my tenure working for the Scottish Rite, an appendant Masonic body, I met a Masonic Brother who was a heldentenor or heroic tenor, who had a gig with the Lyric Opera as an understudy in an upcoming performance of Wagner's Siegfried. It was through Graham's patient tutoring that I learned to appreciate much of what I didn't understand about opera. Through Graham, I met other well-known operatic voices who contributed to my appreciation of the art form as well.

On one occasion, I was invited backstage just prior to the performance of la Traviata conducted by an aging Bruno Bartoletti. It was a fascinating excursion into the tension preceding the downbeat of the overture and raising of the curtain. Bartoletti's wife fussed with his attire, brushing the labels or straightening his tie, while cast members and chorus members, ready and costumed, stood in quiet attention listening to last-minute instructions.

I accompanied Graham to other events, both operatic and social, once taking bass Andreas Silvestrelli and Graham to China Buffet, where both large men were able to satisfy their significant appetites.

As a Masonic Brother, born in the UK and well traveled throughout Europe, Graham also taught me a great deal about Masonic customs in foreign jurisdictions. I also attended a Master Class he presented that was another source of wonder and amazement. Graham was a gifted teacher, having studied under a number of well-known teachers abroad and here in the US at Indiana University.

Lakeview Orchestra

Lakeview Orchestra Music Director Gregory Hughes and Board President Lindsay Brown

My most recent musical excursion was with the Lakeview Symphony Orchestra, a community orchestra of very serious amateur musicians founded by Music Director Gregory Hughes. Under Hughes direction it rapidly became the premier volunteer orchestra in the City of Chicago. Until a couple of years ago, I served on the Board of Directors of Lakeview Orchestra and watched it grow steadily in both stature and financial stability. It now performs at the Athenaeum Theater in Chicago on a regular basis. Hughes adventurous and often eclectic programming taught me a great deal about classical music I had never experienced before. The experience was personally rewarding on a number of levels.

Books and Videos

I do read books about music occasionally. But I should explain that I find books on music theory way beyond my pay grade. Were I a serious composer, arranger or similar creative, they might have relevance, but as it stands, what I know about music theory comes largely from early training in Highs School and University, or later from Youtube, where there are a number great ways to gain an understanding of elementary or even advanced music theory.

In the Youtube search box, try searching for music theory or music composer. The array of choices is broad both in terms of specific music topics such as modes or chord progressions and voice leading, as well as genre.

For books related to music I prefer biographies. For example the biography of Johannes Brahms by Jan Swafford is fascinating reading albeit somewhat controversial. There are likewise biographies of many great composers and musicians, Bach, Beethoven, Haydn, Wagner, and so forth. What seems to be the common thread of interest in all these biographies is the "why" behind the composer or performer's work. We understand the background of why Brahms included that alp horn melody in one of his symphonies, or the significance of what we now call "the fate theme" in Tchaikovsky's Pathetique Symphony. Wagner has especially interesting back stories related to the development of his motif forms of musical expression, and his impact on the world of operatic drama.

A couple of books on my bookshelves are crossover volumes, i.e. books that deal with music and something else, such as neurology or pathology.Two memorable books in this crossover arena are Beethoven's Hair by Russell Martin and Music, the Brain and Ecstasy by Robert Jourdain.

Martin's volume examines the probable medical conditions that contributed to the death of Beethoven, and by extension influenced his late compositions, by a pathological examination of a surviving lock of his hair. Jourdain, on the other hand, examines the contemporary findings of the science of neurology when the human brain is exposed to musical stimulation.

Alex Ross's collection of essays The Rest is Noise deals masterfully with 20th century music and especially the motivations and oppressions of composers living in authoritarian regimes. I have it on audio from the days when I spent a couple of hours commuting by car, and audio books made the trip through Chicago traffic tolerable.

I also note that I have a DVD copy of the film Bride of the Wind that portrays the life of Alma Mahler, wife of the late Romantic Composer Gustav Mahler. It's a fascinating glimpse into the life of a woman who was arguably well ahead of her time, but who was prevented from realizing her great potential as a composer by societal customs. She was romantically involved with a number of fin de siècle Viennese creatives in a variety of fields: art, architecture, and of course, music.

The Great Courses

The single most noteworthy of sources that have left a lasting artistic impression on me has been The Great Courses from The Teaching Company. Originally, these were delivered on DVD, but are now available streamed on demand, making them even more affordable than they originally were.

In general, and specifically musically, anything featuring Robert Greenberg is worth viewing. Greenberg is a master teacher, possessed of deep understanding and knowledge, besides being a composer and musician himself.

My original learning path included these titles:

- The Symphony

- How to Listen to and Understand Opera

- Understanding the Fundamentals of Music

- How to Listen to and Understand Great Music

If you visit the Great Courses website and enter Greenberg into the search box, you'll find even more of his extensive music-related output. Similarly, entering jazz as a search argument will take you to courses dealing with that idiom.

And, of course, there are many, many other fields of human endeavor to pique and tickle a jaded learning appetite. Health, paleontology, history, hobbies, religion, and so on, they seem to cover the major liberal arts bases with rigor and quality content.

Absolutely, highly recommended, especially for those views of a field from 30,000 feet, where context provides the framework that shapes your future understanding.

Conclusion

This essay has described much of the trajectory my life has followed for my first eight decades. Since it has focused largely on music and arts, I have omitted many details or dismissed them with but a few words of prose. For example, I could go on at length for the years I spent as a railroad brakeman; I have many stories and experiences that shaped who I am today thanks to those glorious days of summer days and cool night switching boxcars and helping passengers.

But that wasn't the point of this essay. So I'll save those tales for another day. Meanwhile, I hope you have been inspired to learn more about your favorite music, how it is produced, and the parade of talented, charismatic and often eccentric characters who have shaped it over the centuries.

Likewise, I have omitted some of the smaller episodes of musical involvement in the interest of brevity. I have tried, never-the-less to maintain a cohesive and clear picture of the way events have had a way of influencing my artistic and musical choices. Your influences are likely to be much different from mine, but no less legitimate or without merit.

Here I end with an Authentic Cadence V-I Dominant to Tonic and I hope your own artistic path lands just as satisfyingly on your own dominant chord.